Most radio programmes have news on the hour, and on TV even during the international match half-time break. Only those who want to avoid news have to become active. On Netflix & Spotify however, those who want to listen to or watch the news have to become active – a paradigm shift. Therefore we need “stumbling blocks” for news, especially on streaming platforms. Here are my arguments:

Kategorie: EN

Against a Digital Dictatorship: “Free Information is the Crude Oil of a Living Democracy”

Never before has so much power of opinion been in the hands of so few people. Never before has the free formation of opinion, which is so crucial for our democracies, been in such danger. And never before have the signs of recognising this been so obvious. And yet we do nothing. Why? It is time for an angry outcry. We must act!

Let’s not talk about culture change!

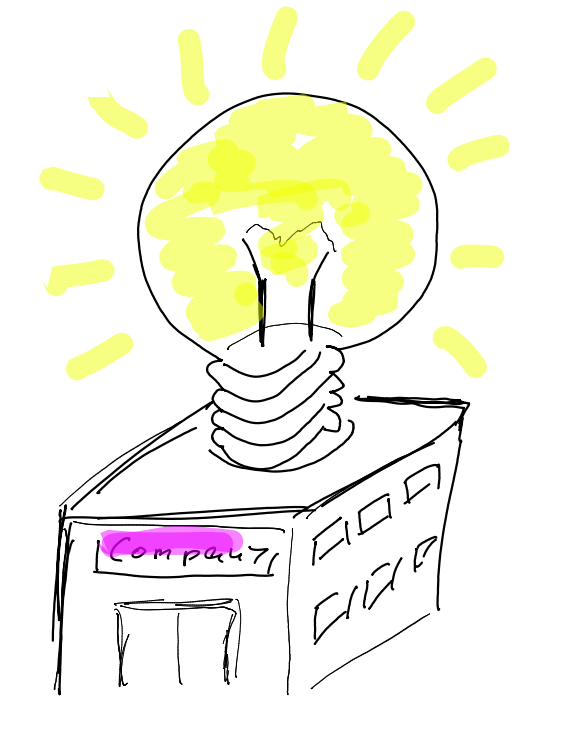

The term “cultural change” is treated by some executives only with keen fingers, and many employees don’t really know what this “cultural change” could actually be about. They sense: Something has to change in my company, but what exactly? Has this term – “culture change” – perhaps already been burned? And what could we use instead?

Why Does Innovation Get Stuck?

Why is innovation stuck? Because media companies often only dare to innovate where it is easy. Possibly banal – but widespread: Because there is no cultural change (transformation), innovation in workflows and products also get stuck.

The Wannabe Company

In the course of a supposed cultural change, some companies become “wannabe companies”: They pretend to be something different from what they are. The consequences are felt by everyone throughout the company. How does this (and what exactly) happen?

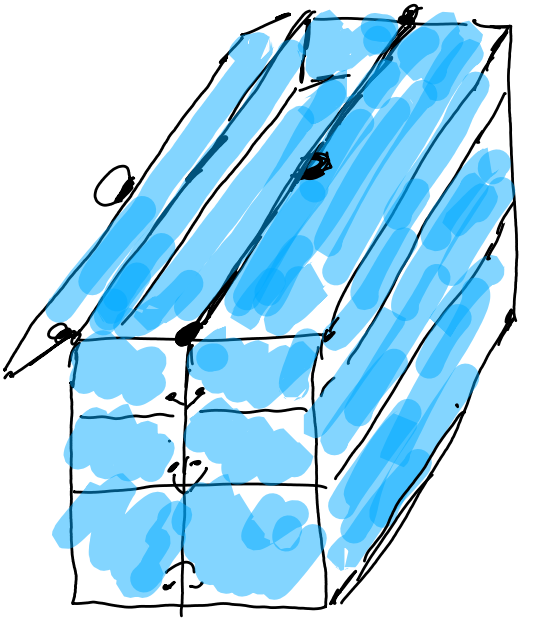

The Transformation Toolbox: What I learned leading a change project

Between 2017 and 2021 I led and designed a major change process. The challenge: We created a new home for a regional, public media brand, including new, redesigned newsrooms, new workflows, and with around 350 colleagues involved. Which tools, ideas and tricks – and which attitude helped us on this way?